| THE STAR Monday, December 4, 2000 Millennium Markers What held Sarawak back? What sort of a mark did the White Rajahs' rule leave on Sarawak? In this week's Millennium Marker, OOI KEAT GIN looks at the combination of place, circumstance and tradition that kept Sarawak a backwater for so long. ACCOUNTS of the fabulous rich soil and great mineral wealth of the island of Borneo were generally believed by Europeans in the 19th century. Such myths were reinforced by works such as John Hunt's On the Great and Rich Island of Borneo and A Sketch of Borneo or Pulau Kalimantan.

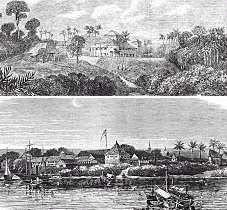

James Brooke, who became the state's first White Rajah after he was granted the fiefdom of Sarawak by the sultan of Brunei in 1841, perpetuated this belief. He claimed that: "the soil and productions ... are of the richest description, and it is not too much to say ... there are not to be found the same mineral and vegetable riches in any land in the world.'' However, Italian botanist Odoardo Beccari, who spent a research sojourn in Sarawak during the 1860s, shattered the myth. "In Borneo,'' he pointed out, "fertility is in a very great measure due to the humus accumulated in the forests, and when this is used up, or carried away by rain or floods, the soil which is left could scarcely be productive.'' Likewise, there was no denying the existence of minerals in Sarawak but the sober reality, according to geologist Theodor Posewitz who undertook a survey in the early 1890s, was that, "although useful minerals were widely distributed, they existed only too often in quantities that would not pay working''. For instance, in the area around upper Sungai Bau, gold, antimony and quicksilver were commercially exploited but with moderate returns only. And while the 1910 petroleum strike at Miri began hopefully, production diminished in less than two decades and prospects of new oilfields were slim. Poor soils aside, Sarawak during the Brooke period was a land unfriendly to large-scale commercial agriculture. The coastal alluvial plain was covered with swampy mangrove forest while mountains dominated the interior of the country. More than three-quarters of the state was under thick, impenetrable rainforest. A myriad rivers and streams dissected the entire state. Agriculture was generally suited only to small farms. The various indigenous communities practised "slash and burn'' subsistance agriculture that produced only hill rice and other food crops. Moreover, the rugged terrain and the numerous rivers posed formidable obstacles to the development of land transportation: roads were limited to urban centres (Kuching, Sibu, Miri) and an 8km railway southwards from Kuching. Rivers had long been the sole artery for transport and communication. River travel assumed significance as coastal shipping was severely retarded by the scarcity of deep, sheltered harbours despite the 720km-long coastline; also, seas were choppy during the landas or rainy season of the north-east monsoon from October to February. Yet river travel was problematic, even deadly, because of rapids, tidal bores, sand bars, shifting channels, shallow sections, and a complicated tidal schedule. Terra incognita and bad publicity Separated by some 700km of the South China Sea from Singapore and the international trade route of the Straits of Malacca, Sarawak was an unknown entity, a terra incognita. Furthermore, Brooke's anti-piracy campaign in the 1840s--which sparked a series of debates in Britain's House of Commons and a Commission of Inquiry in Singapore in 1854--presented Sarawak as a land of marauding pirates and bloodthirsty headhunters. Thanks to the news of the Hakka gold miners' assault on Kuching in February 1857, and of their defeat and subsequent slaughter, Sarawak's image suffered further damage. Such bad publicity put off would-be investors.

A chronic shortage of labour in mining and commercial agriculture did not help matters. The heavy reliance on imported Chinese workers and the high cost of such labour for commercial agriculture (gambier, pepper) and mining (gold, coal, oil) restrained the pace of economic development. Ignorance of Sarawak offered fertile ground for the breeding of wild rumours about the state being a place of headhunting tribes, ferocious animals, and thick, impenetrable, frightening jungles. The massacre and harvest of Chinese heads by Brooke-sanctioned Ibans during the 1857 incident did untold damage to Sarawak's image in the eyes of the Chinese. So, despite the tireless efforts of Brooke--and, later, of his successors--in promoting Chinese immigration, the Chinese were reluctant to come. A cost of living that was high compared with neighbouring territories was another disadvantage. Yet another obstacle to development was Sarawak's remote location off the main trade and shipping routes had nothing to offer--especially in comparison to the British Straits Settlements on peninsular Malaya that boasted the free port giants of Singapore and Penang. Roads and railways connected these two ports to the Malay states in the peninsula's rich hinterland from which raw materials such as tin and rubber were sourced. Hence, British Malaya was a haven for traders, investors and entrepreneurs. Role of the Brooke tradition Notwithstanding becoming a British Protectorate in 1888, Sarawak's negative image persisted. The policies and idiosyncrasies of Brooke's successors, Charles (who ruled from 1868 to 1917) and Vyner (1917 to 1941--when the Japanese took over--and for a year in 1946), further worsened Sarawak's image. Charles's distaste for socialising made him a maverick in political and business circles; this, coupled with his pro-native policies, estranged him from London and Singapore. Vyner was particularly shy and withdrawn and his commitment to traditional Brooke policy served little in improving Sarawak's unfavourable image. Initiated by James Brooke, the policies of the Brooke Rajahs emphasised protecting the interests and rights of the indigenous peoples and the promotion of their well-being. In upholding native interests, the traditional way of life was to be preserved as far as possible. If change was deemed desirable, it was to be introduced gradually to allow the indigenous peoples to adapt and adopt at their own pace. These policies became enshrined as the "Brooke tradition''. Both Charles and Vyner were steadfast to its tenets. Charles was contemptuous of Western capitalists and speculators and afraid they would oppress and exploit indigenous peoples for profit. His land legislation favoured lease over alienation, the refusal to grant large land concessions, and even the banning of the purchase of rubber holdings by "European or Europeans or any individual, firm, or Company of white nationality''. Consequently, Charles appeared as an insufferable despot, anti-capitalist and anti-European; his Sarawak, apparently, was off-limits to Western investors. Vyner was roundly criticised for his gradual and cautious approach to developing Sarawak's economy during the boom years the world experienced in the 1920s. He, too, blocked the inflow of Western investment to prevent the widespread exploitation of the native peoples. Ironically, his policy of favouring family-owned and managed smallholdings over large estates proved to be a wise measure as Sarawak recovered rapidly from the Depression of 1929-1931. But Sarawak's situation still could not compare with that of neighbouring British North Borneo, as Sabah was known then. Although its administration professed to protect native interests like the Brooke Rajahs, it never shied from inviting Western capitalist investment in developing its economy. European tobacco planters were greatly encouraged with large land concessions. By 1941, half of the rubber acreage in British North Borneo was in large European-owned estates; comparatively Sarawak has less than 5%. Although not better off than Sarawak in terms of physical and natural resources, British North Borneo enjoyed a more rapid pace of economic development. To use an analogy, of two equally unattractive people, British North Borneo was better at presenting what few assets she possessed. Furthermore, British North Borneo maintained "an informal and intimate relationship'' with the British Government's Colonial Office in London and close ties with British authorities in the peninsular Malay states even recruiting governors and officers from the prestigious Malayan Civil Service. While Sarawak's physical and geographical disadvantages undoubtedly were the main reasons the state had such a hard time developing, the Brookes also had a role in making Sarawak a backwater. Such was the legacy of the White Rajahs. Ooi Keat Gin is author of Of Free Trade and Native Interests: The Brookes and the Economic Development of Sarawak, 1841-1941 (Oxford University Press, 1997), and World Beyond the Rivers: Education in Sarawak From Brooke Rule to Colonial Office Administration, 1841-1963 (Department for South-East Asian Studies, University of Hull, 1996). He is a lecturer in Universiti Sains Malaysia's School of Humanities and a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society of Britain. |